| demo | ||

| screen | ||

| gui.c | ||

| gui.h | ||

| LICENSE | ||

| Readme.md | ||

GUI

This is a bloat free stateless immediate mode graphical user interface toolkit written in ANSI C. It was designed as a embeddable user interface for graphical application and does not have any direct dependencies. The main design goals is an embeddable immediate mode toolkit that is simple, efficient, portable and lightweight.

Features

- Immediate mode graphical user interface toolkit

- Written in C89 (ANSI C)

- Small codebase (~3kLOC)

- Focus on portability and minimal internal state

- Suited for embedding into graphical applications

- No global hidden state

- No direct dependencies (not even libc!)

- Full memory management control

- Renderer and platform independent

- Configurable style and colors

- UTF-8 support

Limitations

- Does NOT provide os window/input management

- Does NOT provide a renderer backend

- Does NOT implement a font library

Summary: It is only responsible for the actual user interface

Target applications

- Graphical tools/editors

- Library testbed UI

- Game engine debugging UI

- Graphical overlays

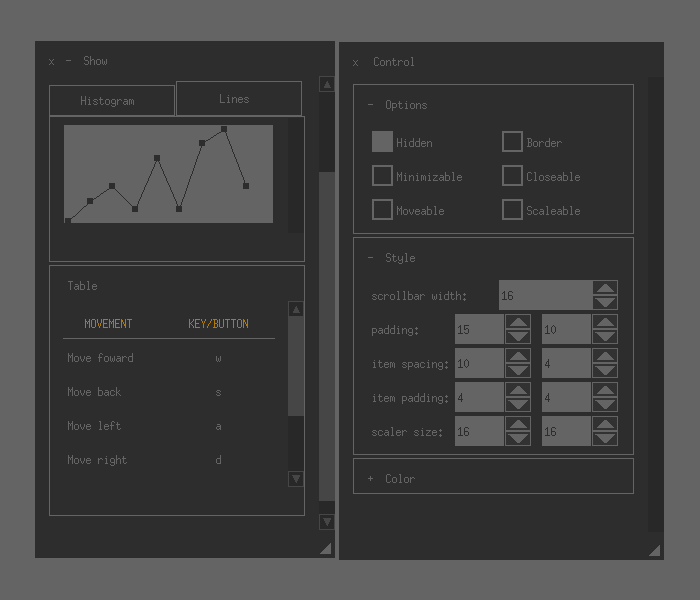

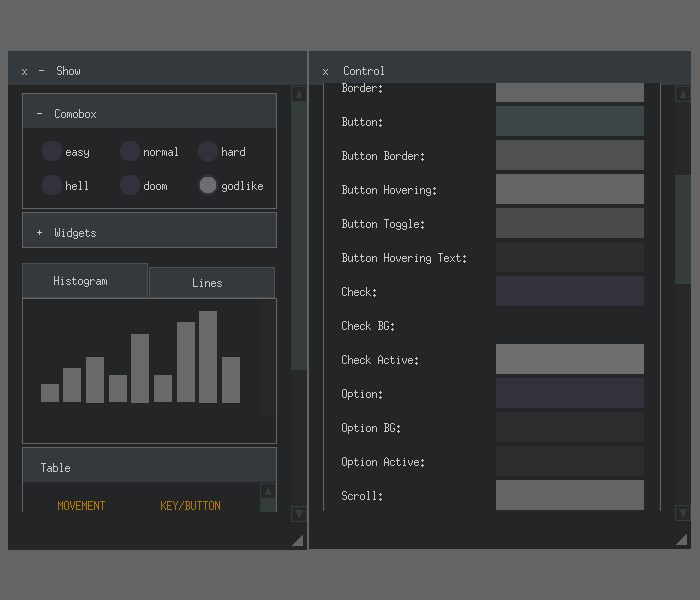

Gallery

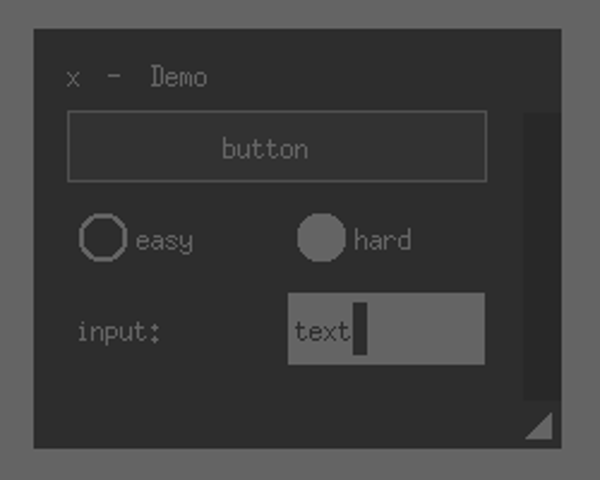

Example

/* allocate memory to hold output */

struct gui_memory memory = {...};

struct gui_command_buffer buffer;

gui_buffer_init_fixed(buffer, &memory, 0);

/* initialize panel */

struct gui_config config;

struct gui_input input = {0};

struct gui_font font = {...};

struct gui_panel panel;

gui_default_config(&config);

gui_panel_init(&panel, 50, 50, 220, 170,

GUI_PANEL_BORDER|GUI_PANEL_MOVEABLE|

GUI_PANEL_CLOSEABLE|GUI_PANEL_SCALEABLE|

GUI_PANEL_MINIMIZABLE, &config, &font);

while (1) {

gui_input_begin(&input);

/* record input */

gui_input_end(&input);

/* transient frame data */

struct gui_canvas canvas;

struct gui_command_list list;

struct gui_panel_layout layout;

struct gui_memory_status status;

/* GUI */

gui_buffer_begin(&canvas, &buffer, window_width, window_height);

gui_panel_begin(&layout, &panel, "Demo", &canvas, &input);

gui_panel_row(&layout, 30, 1);

if (gui_panel_button_text(&layout, "button", GUI_BUTTON_DEFAULT)) {

/* event handling */

}

gui_panel_row(&layout, 30, 2);

if (gui_panel_option(&layout, "easy", option == 0)) option = 0;

if (gui_panel_option(&layout, "hard", option == 1)) option = 1;

gui_panel_label(&layout, "input:", GUI_TEXT_LEFT);

len = gui_panel_edit(&layout, buffer, len, 256, &active, GUI_INPUT_DEFAULT);

gui_panel_end(&layout, &panel);

gui_buffer_end(&list, &buffer, &canvas, &status);

/* draw */

const struct gui_command *cmd;

gui_list_for_each(cmd, list) {

/* execute command */

}

}

IMGUIs

Immediate mode in contrast to classical retained mode GUIs store as little state as possible by using procedural function calls as "widgets" instead of storing objects. Each "widget" function call takes hereby all its necessary data and immediately returns the through the user modified state back to the caller. Immediate mode graphical user interfaces therefore combine drawing and input handling into one unit instead of separating them like retain mode GUIs.

Since there is no to minimal internal state in immediate mode user interfaces, updates have to occur every frame which on one hand is more drawing expensive than classic retained GUI implementations but on the other hand grants a lot more flexibility and support for overall layout changes. In addition without any state there is no duplicated state between your program, the gui and the user which greatly simplifies code. Further traits of immediate mode graphic user interfaces are a code driven style, centralized flow control, easy extensibility and understandability.

Input

The gui_input struct holds the user input over the course of the frame and

manages the complete modification of widget and panel state. To fill the

structure with data over the frame there are a number of functions provided for

key, motion, button and text input. The input is hereby completly independent of

the underlying platform or way of input so even touch or other ways of input are

possible.

Like the panel and the buffer, input is based on an immediate mode API and

consist of an begin sequence with gui_input_begin and a end sequence point

with gui_input_end. All modifications can only occur between both of these

sequence points while all outside modification provoke undefined behavior.

struct gui_input input = {0};

while (1) {

gui_input_begin(&input);

/* record input */

gui_input_end(&input);

}

Font

Since there is no direct font implementation in the toolkit but font handling is

still an aspect of a gui implementation, the gui_font struct was introduced. It only

contains the bare minimum of what is needed for font handling.

For widgets the gui_font data has to be persistent while the

panel hold the font internally. Important to node is that the font does not hold

your font data but merely references it so you have to make sure that the font

always points to a valid object.

struct gui_font {

void *userdata;

gui_float height;

gui_text_width_f width;

};

Configuration

The gui toolkit provides a number of different attributes that can be

configured, like spacing, padding, size and color.

While the widget API even expects you to provide the configuration

for each and every widget the panel layer provides you with a set of

attributes in the gui_config structure. The structure either needs to be

filled by the user or can be setup with some default values by the function

gui_default_config. Modification on the fly to the gui_config struct is in

true immediate mode fashion possible and supported.

struct gui_config {

struct gui_vec2 panel_padding;

struct gui_vec2 panel_min_size;

struct gui_vec2 item_spacing;

struct gui_vec2 item_padding;

struct gui_vec2 scaler_size;

gui_float scrollbar_width;

struct gui_color colors[GUI_COLOR_COUNT];

};

Canvas

The Canvas is the abstract drawing interface between the GUI toolkit and the user and contains drawing callbacks for the primitives scissor, line, rectangle, circle, triangle, bitmap and text which need to be provided by the user. Main advantage of using the raw canvas instead of using buffering is that no memory to buffer all draw command is needed. Instead you can directly draw each requested primitive. The downside is setting up the canvas structure and the fact that you have to draw each primitive immediately. Internally the canvas is used to implement the buffering of primitive draw commands, but can be used to implement a different buffering scheme like buffering vertexes instead of primitives.

struct gui_canvas {

void *userdata;

gui_size width;

gui_size height;

gui_scissor scissor;

gui_draw_line draw_line;

gui_draw_rect draw_rect;

gui_draw_circle draw_circle;

gui_draw_triangle draw_triangle;

gui_draw_image draw_image;

gui_draw_text draw_text;

};

Memory

Almost all memory as well as object management for the toolkit

is left to the user for maximum control. In fact a big subset of the toolkit can

be used without any heap allocation at all. The only place where heap allocation

is needed at all is for buffering draw calls for overlapping panels or defered drawing.

While the standart way of memory allocation in that case for libraries is to

just provide allocator callbacks which is implemented aswell with the gui_allocator

structure, there are two addition ways to provided memory. The

first one is to just providing a static fixed size memory block to fill up which

is handy for UIs with roughly known memory requirements. The other way of memory

managment is to extend the fixed size block with the abiltiy to resize your block

at the end of the frame if there is not enough memory.

For the purpose of resizable fixed size memory blocks and for general

information about memory consumption the gui_memory_status structure was

added. It contains information about the allocated amount of data in the current

frame as well as the needed amount if not enough memory was provided.

struct gui_memory {

void *memory;

gui_size size;

};

struct gui_memory_status {

gui_size size;

gui_size allocated;

gui_size needed;

gui_size clipped_commands;

gui_size clipped_memory;

};

struct gui_allocator {

void *userdata;

void*(*alloc)(void *usr, gui_size);

void*(*realloc)(void *usr, void*, gui_size);

void(*free)(void *usr, void*);

};

Buffering

While a raw canvas provides the ability to draw without any problems, the pure

nature of callbacks is a loss of flow control. You have to immediately

draw a primitive to screen which forces your application to build around the

toolkit instead of controling it. An additional disadvantage of callbacks in this

particular case is that dynamically overlapping panels cannot be implemented since the

drawing order is static. The buffer fixes these problem in exchange for some memory

consumption while still using a canvas internally which adds primitves as

commands into a queue which can later be drawn to screen. Since the buffer

provides a canvas to draw to no additional API changes have to take place.

In true immediate mode fashion the buffering API is based around sequence

points with a begin sequence point gui_buffer_begin and a end sequence

point gui_buffer_end and modification of state between both points.

Buffer and canvas modification before the beginning or after the end

sequence point is undefined behavior.

struct gui_memory_status status;

struct gui_command_list list;

struct gui_allocator allocator = {...};

struct gui_command_buffer buffer;

gui_buffer_init(buffer, &allocator, 2.0f, INITAL_SIZE, 0);

while (1) {

struct gui_canvas canvas;

gui_buffer_begin(&canvas, &buffer, window_width, window_height);

/* add commands by using the canvas */

gui_buffer_end(&list, buffer, &canvas, &status);

}

For the purpose of making multible panels easier to handle, sub buffers were implemented. With sub buffers you can create one global buffer which owns the allocated memory and sub buffers which directly reference the global buffer. The biggest advantage is that you do not have to allocate a buffer for each panel and boil down the memory management to a single buffer.

struct gui_memory memory = {...};

struct gui_memory_status status;

struct gui_command_list list;

struct gui_command_buffer buffer;

gui_buffer_init_fixed(buffer, &memory);

while (1) {

struct gui_canvas canvas;

struct gui_command_buffer sub;

gui_buffer_begin(NULL, &buffer, width, height);

gui_buffer_lock(&canvas, &buffer, &sub, 0, width, height);

/* add commands by using the canvas */

gui_buffer_unlock(&list, &buffer, &sub, &canvas, NULL);

gui_buffer_end(NULL, &buffer, NULL, &status);

}

Widgets

The minimal widget API provides a number of basic widgets and is designed for uses cases where no complex widget layouts or grouping is needed. In order for the GUI to work each widget needs a canvas to draw to, positional and widgets specific data as well as user input and returns the from the user input modified state of the widget.

struct gui_input input = {0};

struct gui_font font = {...};

struct gui_canvas canvas = {...};

const struct gui_slider style = {...};

gui_float value = 5.0f

gui_size prog = 20;

while (1) {

gui_input_begin(&input);

/* record input */

gui_input_end(&input);

value = gui_slider(&canvas, 50, 50, 100, 30, 0, value, 10, 1, &style, &input);

prog = gui_progress(&canvas, 50, 100, 100, 30, prog, 100, gui_false, &style, &input);

}

Panels

To further extend the basic widget layer and remove some of the boilerplate

code the panel was introduced. The panel groups together a number of

widgets but in true immediate mode fashion does not save any state from

widgets that have been added to the panel. In addition the panel enables a

number of nice features on a group of widgets like movement, scaling,

hidding and minimizing. An additional use for panel is to further extend the

grouping of widgets into tabs, groups and shelfs.

The panel is divided into a struct gui_panel with persistent life time and

the struct gui_panel_layout structure with a temporary life time.

While the layout state is constantly modified over the course of

the frame, the panel struct is only modified at the immediate mode sequence points

gui_panel_begin and gui_panel_end. Therefore all changes to the panel struct inside of both

sequence points have no effect in the current frame and are only visible in the

next frame.

struct gui_font font = {...};

struct gui_input input = {0};

struct gui_canvas canvas = {...};

struct gui_config config;

struct gui_panel panel;

gui_default_config(&config);

gui_panel_init(&panel, 50, 50, 300, 200, 0, &config, &font);

while (1) {

gui_input_begin(&input);

/* record input */

gui_input_end(&input);

struct gui_panel_layout layout;

gui_panel_begin(&layout, &panel, "Demo", &canvas, &input);

gui_panel_row(&layout, 30, 1);

if (gui_panel_button_text(&layout, "button", GUI_BUTTON_DEFAULT))

fprintf(stdout, "button pressed!\n");

value = gui_panel_slider(&layout, 0, value, 10, 1);

progress = gui_panel_progress(&layout, progress, 100, gui_true);

gui_panel_end(&layout, &panel);

}

Stack

While using basic panels is fine for a single movable panel or a big number of static panels, it has rather limited support for overlapping movable panels. For that to change the panel stack was introduced. The panel stack holds the basic drawing order of each panel so instead of drawing each panel individually they have to be drawn in a certain order.

struct your_window {

struct gui_panel_hook hook;

/* your data */

}

struct gui_memory memory = {...};

struct gui_memory_status status;

struct gui_command_buffer buffer;

gui_buffer_init_fixed(buffer, &memory);

struct gui_config config;

struct gui_font font = {...}

struct gui_input input = {0};

struct your_window win;

gui_default_config(&config);

gui_panel_hook_init(&win.hook, 50, 50, 300, 200, 0, &config, &font);

struct gui_stack stack;

gui_stack_clear(&stack);

gui_stack_push(&stack, &win.hook);

while (1) {

struct gui_panel_layout layout;

struct gui_canvas canvas;

gui_input_begin(&input);

/* record input */

gui_input_end(&input);

gui_buffer_begin(&canvas, &buffer, window_width, window_height);

gui_panel_hook_begin(&layout, &win.hook, &stack, "Demo", &canvas, &input);

gui_panel_row(&layout, 30, 1);

if (gui_panel_button_text(&layout, "button", GUI_BUTTON_DEFAULT))

fprintf(stdout, "button pressed!\n");

gui_panel_hook_end(&layout, &win.hook);

gui_buffer_end(gui_hook_list(&win.hook), buffer, &status);

/* draw each panel */

struct gui_panel_hook *iter;

gui_stack_for_each(iter, &stack) {

const struct gui_command *cmd

gui_list_for_each(cmd, gui_hook_list(h)) {

/* execute command */

}

}

}

FAQ

Where is the demo/example code?

The demo and example code can be found in the demo folder. There is demo code for Linux(X11), Windows(win32) and OpenGL(SDL2, freetype). As for now there will be no DirectX demo since I don't have experience programming with DirectX but you are more than welcome to provide one.

Why did you use ANSI C and not C99 or C++?

Personally I stay out of all "discussions" about C vs C++ since they are totally worthless and never brought anything good with it. The simple answer is I personally love C and have nothing against people using C++ especially the new iterations with C++11 and C++14. While this hopefully settles my view on C vs C++ there is still ANSI C vs C99. While for personal projects I only use C99 with all its niceties, libraries are a little bit different. Libraries are designed to reach the highest number of users possible which brings me to ANSI C as the most portable version. In addition not all C compiler like the MSVC compiler fully support C99, which finalized my decision to use ANSI C.

Why do you typedef your own types instead of using the standard types?

This Project uses ANSI C which does not have the header file <stdint.h>

and therefore does not provide the fixed sized types that I need. Therefore

I defined my own types which need to be set to the correct size for each

platform. But if your development environment provides the header file you can define

GUI_USE_FIXED_SIZE_TYPES to directly use the correct types.

Why is font/input/window management not provided?

As for window and input management it is a ton of work to abstract over all possible platforms and there are already libraries like SDL or SFML or even the platform itself which provide you with the functionality. So instead of reinventing the wheel and trying to do everything the project tries to be as independent and out of the users way as possible. This means in practice a little bit more work on the users behalf but grants a lot more freedom especially because the toolkit is designed to be embeddable.

The font management on the other hand is litte bit more tricky. In the beginning the toolkit had some basic font handling but I removed it later. This is mainly a question of if font handling should be part of a gui toolkit or not. As for a framework the question would definitely be yes but for a toolkit library the question is not as easy. In the end the project does not have font handling since there are already a number of font handling libraries in existence or even the platform (Xlib, Win32) itself already provides a solution.

References

- Tutorial from Jari Komppa about imgui libraries

- Johannes 'johno' Norneby's article

- Casey Muratori's original introduction to imgui's

- Casey Muratori's imgui panel design(1/2)

- Casey Muratori's imgui panel design(2/2)

- Casey Muratori: Designing and Evaluation Reusable Components

- ImGui: The inspiration for this project

- Nvidia's imgui toolkit

License

(The MIT License)